Why NFTs are just like stories

Blockchain, non-fungible tokens, and their relationship with music

I have long been fascinated by Walter Benjamin’s essay “The

work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction” (no relation!) and the way in which it relates to music. The new technology of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and their application to

digital art is, I think, strongly resonant with the ideas set out in Benjamin’s essay. While NFTs are primarily (but not exclusively) associated with visual digital art, I as a composer (that is, an artist in a musical

context), am naturally curious about the application of NFTs to music.

Benjamin begins his essay by quoting an earlier one by Paul Valéry, La Conquête de l'ubiquité (1928), including this:

“We must expect great innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts, thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps even bringing about an amazing change in our very notion of art.”

A change in our very notion of art? We shall see!

Benjamin’s essay describes “aura” as something possessed by an artwork, intrinsic to its artistic authenticity, and which gives it cultural authority. He asks how aura can exist when the work of art is perfectly mechanically (or we might ask: digitally) reproduceable – when there is no difference between the original and the nth copy?

Fungibility

This is the essence of “fungibility”, that is, my copy of X has the same value as your copy, and both are identical to the original. In monetary terms: my £1 is no different to yours. If I am to transfer £1 to your bank account, it doesn’t matter which of my pounds I transfer.

But say I own a limited edition £1 coin. There were only 100 minted. They have physical characteristics that mark them as part of that limited minting. The value is greater than £1, perhaps it’s £1.50, that makes the “limited” aspect, or rarity value, worth 50p, because I could still use the coin as a regular, fungible £1 coin. If I am a collector of limited-edition coins, the rare £1 is less fungible – I certainly would not exchange it with an ordinary £1 coin, and I would only exchange it with another from the limited run if that other was in equally mint (sorry) condition. Perhaps the limited run is numbered – reducing the fungibility further, because the coin with serial number #1 is probably more valuable than serial #93. Therefore, the coin with serial #1 has a greater “aura”.

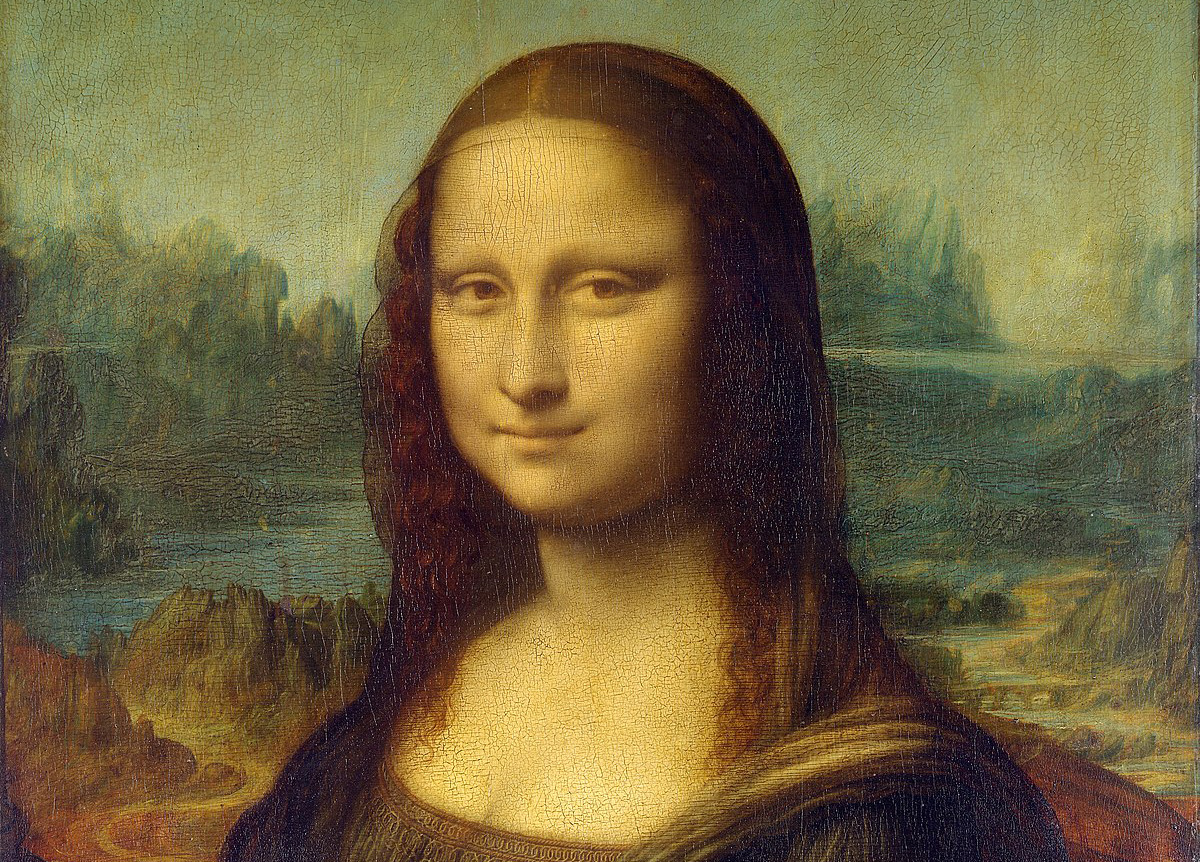

Is the Mona Lisa fungible? No, there is only one. There are many copies (on mugs, t-shirts, postcards, gifs, websites like this…), but only the original has the aura of originality and authenticity, and therefore the value of the original. It could be exchanged for money in an auction, but it’s the money that is fungible, not the Mona Lisa. It wouldn’t matter which particular billion Euro was exchanged for the artwork.

What about digital art, then? What if the artwork exists only in a form that can be endlessly and perfectly copied? Walter Benjamin says:

“Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: Its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be located.”

In his essay, he explores this problem in connection with film and photography, but the problem also exists for music recordings, and in the modern day, the problem exists for digital art and digital literature (such as ebooks).

Electronic music

Suppose I make a recording on my computer using Ableton and some synthesizers. I might apply some digital effects and then add some field recordings, then manipulate those too, blending them with the synthesizers. The finished composition exists purely as a digital file on my computer – a collection of 1’s and 0’s, and further down, just a collection of atoms on my hard drive arranged just so.

Now, surely those 1’s and 0’s, and those atoms, are fungible. One 1 is interchangeable with another 1, and one silicon atom is the same as any other. This means that I can make a digital copy of the file which is identical to the original. I better do that, in fact, because at the moment, if my hard drive fails, then I lose that file and it’s gone forever! And so, we create backups of our digital creations, such as word processor documents, photos, or pieces of digital music. My backup is, by definition, an interchangeable copy of my original work. If I lose the original work, it doesn’t matter, because I have a backup that is an identical copy of the original. And I can copy that backup as many times as I like.

Suppose I upload it so you can listen to it. It goes on YouTube, iTunes, Spotify, and Soundcloud. There's essentially no difference between them - regardless of where you access it, aside from compression, it's identical to the original. But if you object that compression robs the work of its authenticity, then howabout I give you a link to a 24 bit, 192kHz WAV for you to download to your disk, same file I exported from Ableton, same file that a thousand others have downloaded?

A fungible artwork

What we have now, in other words, is a fungible artwork. While there was an original file, it had no “aura” of originality in the sense that the original Mona Lisa has “aura”. There is no way to tell the backup from the original. The artwork exists independently of its medium.

This presents (at least) two problems…

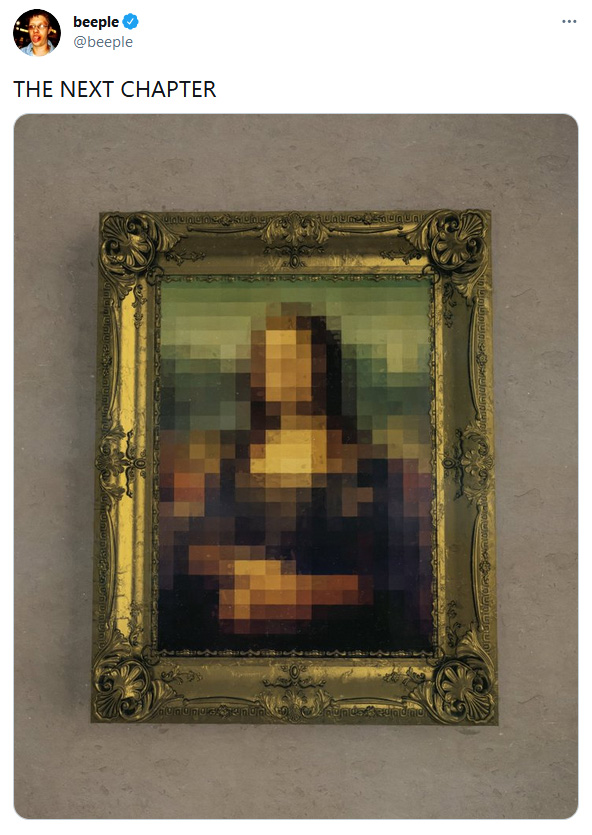

Problem #1: How can a digital artist create a unique artwork?

Their earthly concern might be simply the need to sell the artwork, like Van Gogh selling his (non-fungible) paintings in exchange for some “reassuringly expensive” Stella Artois. Beer, of course, is a fungible commodity – we often talk of the software that is free “as in beer” but not “as in speech” (a whole other, but related, issue).

Problem #2: How is the artwork special?

How can the artist’s customer (say, a collector) know that the piece is special? That it has the “aura” imbued to it by the artist? That it is the original Mona Lisa, not one of the millions of copies sold every year as postcards and mugs?

Cult and exhibition value in art

Walter Benjamin identifies two types of value in an artwork: cult value and exhibition value.

Cult value is bound up with ritual; what matters is that the art exists, not that it can be seen. Exhibition value relates to the audience’s pleasure of gazing upon the artwork, and not its

ritual aspect. Art can potentially have a degree of both, in amounts that can change; over history, religious art (for example) has generally lost cult value and gained exhibition value (think of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel).

Now, this might seem of little relevance to digital art, but Benjamin describes the creation of cult value from ritual and the fabric of tradition, and then describes the ritualisation of the act of mechanical reproduction. He explains that this shift frees the work of art from its dependence on ritual. Previously, the uniqueness (aura) of an artwork was connected to

reproduction of art: aura is lost through the perfect mechanical reproduction of the original. But now, reproduction itself is ritualised, and cult value is generated through that ritual.

Take film. The audience might feel that they identify with an actor placed in a dramatic situation. However, their identification is not in fact with the actor, but with the camera. And it is the camera that creates the reproduction (of the drama), and so it is the act of mechanical

reproduction of the art (i.e. the filming, the mise-en-scène) which generates cult value and aura, not the artistic acts that are being filmed (the acting, lighting, writing, and so on). Thus film has power and aura as art even though it can be infinitely and perfectly copied – even though it is fungible, in other words.

Returning to the more prosaic financial problems facing the artist and their audience that arise from perfectly reproduceable art. The solution in the case of music (and, indeed, software, digital photos, and every other kind of digital asset) has been to license the use of the artwork. I can license my completely fungible digital recording for you to use in your 2021

advert in Brazil, but if you then use it in your 2022 advert in Australia without a fresh agreement, that’s against the terms of the licence and you’re a bad person.

I could discuss soundalikes, rearrangements, and other forms of plagiarism here, and the legal aspects, but we’re concerned with the original art today, so I won’t. Another time, maybe.

So, licensing and paperwork is a solution. But there is a new solution on the block, and that’s a magnificent pun, for the solution is blockchain technology.

Enter the blockchain

Cryptocurrency is a new(ish) type of currency that depends on blockchain technology. An explanation of how cryptocurrency and blockchain works is beyond the scope of this article (look here for an intro), but taking the Bitcoin (BTC) currency for example:

BTC are fungible. One BTC is worth the same as another in the same way that my £1 is worth the same as your £1.

BTC can’t be copied. The blockchain is essentially a list that proves who owns which BTC, and as everyone who owns BTC has a copy of the list, it’s impractical to change every copy of the list at once and create new BTC by simply adding one against my name on the list or

change ownership of BTC without consent by modifying the list. Each “block” of transactions in the “chain” of transactions is cryptographically linked to the previous block.BTC ownership is secure. Rather than depending on trust, it’s a “trustless” environment. Think of a BTC as gold in an anonymous lockbox in a bank vault. Whoever has the key can get in and access the gold. So if you lose your key, although everyone knows that someone owns the gold in that lockbox, you can’t prove you own it without the key. This keeps on happening with Bitcoin.

These aspects of cryptocurrency potentially make it useful for giving digital art intrinsic value, or “aura”. I can create a token (a bit like a cryptocoin or a special software program: if you’re into this stuff, you might recognise dApps and Ethereum here), and prove my ownership of it, because it lives on that special list (the blockchain). The token is unique and can’t be copied – or at least, while the 1’s and 0’s can be copied, my ownership of that token can’t be copied to someone else. No matter how many copies of the list exist, only I have the key to prove that my bit of the list belongs to me. And I can sell that key to someone else, so they can own it. This gives the digital artwork the necessary scarcity value that (perhaps) imbues aura. The

token can only exist once in the blockchain.

This technology solves a few further problems that aren’t solved by existing copyright law, such as:

The artist can sell “shares” in an artwork and can easily trade those shares. By contrast, trading a fraction of the rights to (say) a recording is difficult and legally technical.

The artist can earn royalties each time the artwork (or the token) is traded. This can be built into the blockchain or cryptocurrency itself. In the old world, while my rights to earn royalties on each transaction could be enshrined in law, it’s hard to enforce across jurisdictions, and it’s easy to keep a change of ownership of an original painting (for example) secret.

What about music?

Where does all this lead for music?

There are many potential applications, and I can certainly see this tech transforming royalty collection, which is still a frustratingly manual process prone to error and even fraud, ripe for further digital transformation.

As for aura and perfect mechanical reproduction – well, I’m not convinced that music has “aura” to begin with, not in the sense that an original work of visual art does. But without a doubt, the act of reproduction of music has aura – both cult and exhibition value, in Walter Benjamin’s terms – think of the way in which certain orchestras and concert halls are venerated (cult value), or the recordings or reputations of certain conductors considered

almost on a par with a prophet (Toscanini, anyone?), and there’s no doubt as to the exhibition value of seeing musicians perform.

But what about the actual composition? Not the performance – the composition.

The physical and acoustic artefacts associated with a composition have aura: an original Beethoven sketch for example, or the experience of being in the room for a live performance (which is a form of ritual). But this is still not the composition.

For me, the act of musical composition is more akin to discovery out of exploration than the creation of a visual artwork. I can prove that this music exists if I order things like so, in the same way that I can prove that America exists by travelling across the ocean like so. Columbus and Beethoven are remembered, but America can easily be reached by anyone with a suitable ship and navigation skills, and anyone with a piano and ability can play Für Elise. But discovering America or Für Elise can only be done once…

…so long as you can prove you were the one to discover it, and not Leif Eriksson!

Stories

Perhaps this is where NFTs can help. I create a record of my journey as a token, and secure it in the blockchain, where it exists as proof of my work for as long as the blockchain exists.

To this extent, the blockchain is no different to the chain of storytelling that has passed down the legend that Eriksson, or Columbus, discovered a far-off land and named it America (or San Salvador, to be precise, at least in the case of Columbus). There might only be 7 basic plots, but storytellers have for thousands of years discovered new stories to tell within them.

In the same way, new generations might experience Für Elise by sitting around a musician and understand that once, in the distant past of the early 19th century, a man called Beethoven sat down and discovered that these notes, arranged just like this, would produce this music,

and named it Für Elise. The story of that discovery – that composition – has been passed down the chain to you, dear listener. Long may you enjoy it and long may that particular “blockchain” continue to exist.